MULID

SUFI FESTIVAL IN EGYPT

THE CHAOTIC JOY OF SUFI SAINTS FESTIVALS IN EGYPT AND THE SHA’BI CULTURE OF EGYPTIAN STREETS

n the eyes of an educated liberal, the traditional culture of the Middle East is synonymous with backwardness, superstition and oppression. Fossilized social structures limit freedom. Fortunately, awareness exists to suppress ignorance, and democracy to oust oppression. Heritage, dressed in colourful clothes, may appear in expensive restaurants accompanied with the sounds of traditional instruments… The over eight-hundred-year-old tradition of Sufi festivals in Egypt adds a bit of a joyful diversion to this narrative.

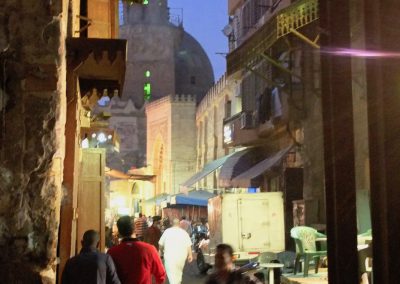

We sit on plastic-covered seats and relentlessly smoke cigarettes, blowing smoke through the open windows. The taxi arduously meanders through the southern parts of the Islamic Cairo. We pass by Sayyida Zainab – a district named after the Prophet’s granddaughter who is supposedly buried here, and through the maze of streets surrounding the old Ottoman necropolis. The medina is historically divided into smaller hermetic districts, where all inhabitants know each other. Life in these districts vibrates twenty-four hours a day, and the hurly-burly of the chaotic network of streets and lanes feels like blood flowing rapidly along arteries. Cairo is a thousand-year-old city, therefore its social space is very complex; this complexity is especially felt in its old parts. Unlike the guarded estates, the medina is alive and each of its lanes satisfies the numerous needs of the residents. Entertainment, food, commerce, prayer and services are all within reach. The Egyptian middle class is ashamed of the old Cairo which has fallen to pieces, yet newcomers from the orderly but lifeless cities of the West are fascinated with it. All this, flooding with never-silent traffic. By day, approximately twenty million people swarm through the metropolis; four million of which are commuters who return to their suburbs at night.

We are trying to plough through the heavy traffic. We see a truck decorated with lights and producing the wall of sound from scuffed speakers as if to make its way – this is the first mark of the festival taking place a dozen or so turns away. The drummer on the trailer relentlessly beating the baladi (folk) rhythm is almost as loud. We leave the taxi near the al-Rifa’i mosque and the citadel. The Sufi carnival completely annexed a dozen blocks. This is not a religious holiday in a strict sense. It is also folk entertainment, with blurred limits. Besides the Sufi, there are street artists, costume parades, carousels, shooting ranges and the entire colorfully flashing fair-ishness of the folk feast.

According to the Sufi doctrine, festivals are open to all participants, including those who are openly hostile to Sufism but are attracted by the very atmosphere of street carnival. The ubiquitous speakers emit distorted, hypnotic arrangements, from time to time interrupted by the singer’s lament. The youth from the neighborhood, intoxicated with anything, dance bathed with colorful lights and fall into a trance shoulder to shoulder with members of the Sufi brotherhood (tariq). Hordes of kids, running unheeded, throw stones at passing cars, while next to them free food that brings blessing (baraka) is distributed, and daddies with children try to shoot the largest teddy bear at the shooting range. Although the festival is participated by several thousand people, the entire confusion is not noticed just a few streets away and most residents of the Cairo metropolis are not aware of it.

Mulid is the Egyptian pronunciation of the Arabic word mawlid, which means birth or birthplace and is most often used in the context of the birth of the Prophet Muhammad (Mawlid al-Nabi). This annual festival is celebrated in most Muslim countries except Saudi Arabia and Qatar, where it is forbidden by the doctrine of Wahhabism. In Egypt, the word “mulid” is also used to describe a completely different phenomenon, such as difficult-to-define street festivals celebrating the holy men of Sufi and Christian traditions (in the past also Jewish tradition). Here, for a change, the celebrated event is not the day of birth of a holy man but the day of his death and transit to another world. Dates of most mulids are set on the basis of the Muslim lunar calendar and each year they move about ten days ahead of the current solar calendar, which may cause some organizational difficulties for visitors from outside the Middle East who want to celebrate the day of birth of a Sufi saint.

Unlike in the Orthodox Christianity or Catholicism, there is no canon of saints in Islam, though the Quran mentions the Friends of God (Awliya Allah) – those, who fast for the entire year, and not only in Ramadan, who deepen their esoteric knowledge, who can see thoughts of other people, who are healers and miracle-makers (karamat), who talk to God in a way that is inaccessible to others. The Quran describes them as mediators between people and God. Anyone can be wali – a saint – not only sheikhs (masters, leaders) familiar with holy scriptures, or medieval founders of the largest brotherhoods. Women are also worshiped, such as sheikha Nur al-Sabah, whose tomb is situated in the city of Tanta, or sheikha Sukkaniyya, the patron of unmarried maids. Becoming a saint can also be a fate or God’s will. There is a tomb of a little boy in old Cairo frequently visited by worshippers and a common objects of veneration are madmen “drunk with God”, in Egypt called majadhib – people deprived of their mental abilities in result of sudden enlightenment – are a common objects of veneration. Ahmad Radwan, a Sufi mystic admired by President Nasser, cautioned against asking a majadhib for a prayer, because – as he claimed – it would be a prayer for misery or illness, the states conducive to entering paradise. Streets and lanes of old Cairo, small towns and villages are full of shrines and places of worship. This spiritual geography is particularly well known to women. Places that emit blessings become important reference points during a daily navigation in irregular urban landscape of the Middle East.

The development of the cult of saints in the Muslim world is associated with the expansion of Sufi mysticism. Pilgrimages and festivals at graves of saints have become an important part of Muslim piety in the twelfth century. All cities, towns and villages in Egypt have a day when they venerate a local saint, but mulids dedicated to over twenty Muslim and about seven Christian saints attract real crowds of pilgrims from around the country. The largest Egyptian festival is al Sayyid Ahmad al-Badawi mulid in Tanta, visited by almost half a million participants annually. The festivalreported here, taking place at the tomb of al Sayyid Ahmad al-Rifa’i is much smaller, but it is organized by one of the oldest Sufi brotherhoods in the world, ar-Rifa’iya. Members of the brotherhood are famous for their ascetic practices and body mutilation, and until recently, snake shows could be seen during the mulid. The special role of these reptiles in the ar-Rifa’iya tradition seems to reveal mutual infiltration of old Middle Eastern beliefs and influences of religions much older than the Abrahamic tradition.

Egyptian mulids belong to the festival tradition widely spread in the Muslim world. Similar events take place in Morocco (mawsim), Turkey (mevlud), East Africa (hauli), Indonesia (hawl) and the Indian subcontinent (urs). Despite its magnitude, the festival tradition is now fiercely attacked and criticized by Islamic reformist movements (mainly Salafi) on the one hand and by progressive, modern elites on the other. Participants of mulids associate the festivals with love, joy, blessing and freedom, while in public discourse and in the media they are identified with dirt, superstitions, laziness, pettycrimes and chaos. In modern Egypt, the number of participants of mulids has been gradually decreasing, and the phenomenon is slowly pushed to the fringe of social life.

SHA’BI – THE EGYPTIAN STREET CULTURE

Mulids usually last about a week and culminate with The Great Night (al-layla al-kabira). During these seven days, streets come alive at night and rest during the day. The events always begin and end with a carnival procession (zaffa), which is a separate entity having little to do with Sufi narrative. Preparation of the processions is the domain of the folks of a district in which the tomb of a saint is located. The aesthetics of this event, so hard to grasp, was quite accurately presented by Samuli Schielke in his book Perils of Joy. He described the grotesque carnival-like procession consisting of a cavalcade of vehicles with incredible improvised installations, the local society’s cause for pride. Some of them displayed boxing matches, transvestite weddings, copies of shrines on the platforms of trucks, or groups of pseudo-militaries led by a pseudo-dictator with a megaphone in his hand, promising everyone a grand future with better telephone lines, clean drinking water, and a new brothel.

Mulids express the free morals of the Egyptian streets. Sha’bi culture materializes here in the form of crowds of men and women in corner coffeehouses, which often contract popular musicians for the occasion. Sha’bi musicians specialize in weddings, and such is the atmosphere pouring out of the coffeehouses, mixing with even louder concerts of the munshids, Sufi singers. There are still coffeehouses serving alcohol during mulids, and while wandering around the festival streets, one can smell the aroma of high-quality Egyptian hashish. Up to the 1990’s, the greatest attraction of the festivals were the performances of dancers, full of uninhibited eroticism and with a large representation of transvestites. The bad reputation associated with such aspects of the festivals was, of course, one of the issues most frequently raised in the public debate concerning mulids.

For a short while, the crowd liberates itself from the powerful oppression of traditional divisions and hierarchical constraints. The street “senses” the possibility of free expression, and becomes a stage of subversive acts and behaviors breaking the established norms. In a charged atmosphere, sexual tension and aggression appear next to bliss, joy and love. On the one hand, there is the mood of friendship and solidarity, meals are served, and people drink tea and smoke tobacco together. On the other hand, boys throw stones and young men, completely lost in the Sufi trance spinning, and a moment later exploding with aggression towards other men or groping women in the crowd. Momentary relaxation of the tensions that rule Arab daily life causes that for many participants the atmosphere of mulids is sexually charged. There is no doubt that young people are mainly attracted by this aspect of festivals. Young girls launch their seductive powers, put on makeup, wear tight jeans and peroxide their hair. In Egypt it is uncommon to see a girl dancing ecstatically all night long on the street. Men stare at the dancer’s anatomy but they know it is not allowed to come closer or even exchange a glance with her because of religious context of the event.

Youngsters, however, see it differently; they attend mulids for a specific purpose. Sometimes people get stuck in narrow passages between squares and lanes. In such places, young men lurk for groups of girls passing by; they want to brush or touch their bodies unnoticed by anyone. Stallholders standing on boxes and policemen carefully watch pushy youngsters and if cold water poured on their backs is not able to cool down their fervor, police batons can be used. However, young girls are not just victims here. According to Anna Madoeuf, a French researcher who participated in many mulids, they often enjoy topsy-turvy on squares. Groups of young girls, out of sight of their watchful parents, freely explore mulids, and cross such street “blocks” in excitement, laughing and screaming.

A mulid is a part of reality in which thieves and lawyers, prostitutes and priests are temporarily equal

Physical contact, dance, alcohol, drugs, sexy costumes, parodying the institution of marriage or cheerful gender experiments – all of them result from the temporary suspension of boundaries. Everything that has been thrown out of the city walls or pushed into oblivion returns to it. In the unique carnival space-time, behaviours attributed to groups excluded from the project of modern society are accepted. Indeed, various forms of excesses are accepted during mulids. Everyone is a guest at the celebration of a saint’s anniversary and this perspective creates a certain exception in social relations. The festivals are what they should be: a space-time of transgression, in which family and social control is loosened. A mulid is a part of reality in which thieves and lawyers, prostitutes and priests are temporarily equal. Whoever you are, mulid space allows you to experience freedom – however, mind that you enter at your own risk. Officers of uniformed services used to avoid festivals, albeit this situation has been recently changing due to the risk of attacks by radical Islamic militias manifesting hostile attitudes to Sufism and mulids.

SUFI

In Egypt, Sufi brotherhoods are perceived as a form of Islam practiced in the country and poor urban districts. Representatives of the Egyptian establishment and educated children of the Cairo medina situate the Sufis somewhere between village superstitions and the ambivalent sha’bi culture. After the Arab Spring and the overthrow of President Muhammad Mursi, the Sufi brotherhoods organized themselves politically and began to be perceived as a folk remedy against the threat of Islamic extremism.

I am not much interested in brotherhood taxonomy and in copying or creating larger narratives about them. Instead of making such descriptions or forcing definitions of boundaries between religious orthodoxy and the so-called folk practice or magic, I would rather present some loosely selected images and phenomena related to the very essence of this tradition. The essential aspects of Sufism which are not obvious in written accounts, are often revealed during festivals at the tombs of the Friends of God.

On the metaphysical plane, the centre of festivals is the tomb of a saint protected by a decorated wooden grating (maqsura) – touched by countless pilgrim hands – looking as if washed by water flowing over it for hundreds of years. This is the source from which baraka – a blessing offered to the world by the deceased saint – radiates. It pours from the tomb (darih) onto the square under the mosque and flows through the streets and squares establishing a sacred space (barzakh), which is the place (or time) between physical death and the day of final judgment. Saints, angels and ordinary people coexist here and can communicate without limitations. The saint, although buried in the tomb, is not dead; he participates in his feast and is ready to help mortals. Baraka, amplified by the figure of the saint, is the main aspect of a mulid attracting pilgrims from all over Egypt. The sick come to be healed, the poor hope for a miraculous change in their fate, and the lost expect regaining clarity. Staying within the range of the impact of baraka is a revitalizing experience for everyone.

Sufi saints are obviously not the only source of baraka. For many Muslims, the letters written in the Quran form not only a script but also a field of divine energy. According to the collections of Hadith, the Prophet Muhammad recited some suras directly into the palms of his hands and then rubbed his body with them to provide him health and protection against witchcraft (sahir). In Islam, the holy book is still more than a text to be contemplated, although Islamic reformist movements or educated elites of Egypt would be glad to reduce it to this function. A micro-copy of the Quran hanging from the taxi mirror – with letters too small to be read – is a clear evidence of such an attitude. Michael Muhammad Knight – a controversial American convert who gained fame as author of the novel The Taqwacores, presenting a utopian fusion of Islam and punk rock – claims in his latest book Magic in Islam that the Quran for Muslims is something like the Bible and the Eucharist in one for Catholics: it is an embodied blessing permeating the matter like the Force – a metaphysical power in the Star Wars movie series.

If these several sentences could exhaust the topic of baraka, perhaps many people would not find anything special in it. Many traditions or religious institutions promise miraculous healings and changes of fate, and psychology has long appreciated the power of self-suggestion. What makes Sufi festivals in Africa and Asia so unique is that baraka pouring from the tombs blurs the boundaries between the sacred and the profane: the accepted categories decay and the established divisions are temporarily suspended. Mosques become dining rooms and bedrooms for male and female pilgrims. Squares in front of temples are transformed into arenas of popular entertainment. Young women dress up, make up and go out to have fun in their groups free from the watchful eye of patriarchy. The surrounding streets are covered tightly with tents, in which women and men, politicians and dervishes, businessmen and beggars freely eat, smoke and talk. Doors of colourfully decorated houses are open to unexpected guests, and local residents celebrate together with pilgrims sleeping for a week under their windows. On the streets of a modern city – fuelled by the ideology of development and profit – money and food are distributed gratuitously, because when people are selfless, baraka keeps flowing.

The wide range of influence of the baraka marks an ambivalent area – worrying for some and liberating for others. This is the quintessence of Sufi mysticism, which despises attachment to forms, established divisions, simple obligations and prohibitions. The specific atmosphere of Sufi festivals, regardless of the country they take place in, is difficult to convey in words. Two images come to my mind, memories of events where physical barriers and bars disappeared under the pressure of this enthusiasm…

The first image is ziyara, a ritual visit to a tomb in an Egyptian mosque taken by every pilgrim to greet the saint whose jubilee is celebrated. However, the mosque, similar to many other Egyptian temples, this time looked completely different. A pensive mood, peace, whispers and a quiet step on the carpet so as not to disturb the others – so typical of mosques – are absent during mulids. Bars separating the women’s and men’s sections disappear just after the last evening prayers on the first day of the mulid, when a crowd of men, women and children annexed the temple, transforming it into a permanent outdoor birthday party. The space was tightly filled with celebrating people. Someone was handing out loaves of bread, people greeted each other affectionately, loud cries and laments were heard, and a hypnotic dhikr (sufi “rememberance” ritual) of a dozen people led by the singer took place somewhere in the middle of it all. The procession of men and women pressed against the passage leading to the tomb; everyone wanted to pay homage to the saint and encircle the grave situated under the dome. The atmosphere was really heated. Everyone could be absorbed by the crowd, as if pulled by a wave, and there was no way to step back. Inside the small tomb people constantly pass counter-clockwise. Those who advanced from the outside would produce overpressure, forcing rotation around the grave; those who had already completed the full cycle were pushed out through the tight passage. Inside, the main task of each participant was to squeeze through the tightly packed procession and touch the maqsura for a while, at the same time loudly greeting the saint. Each of them did it in their own unique way. The cramped hall resonated with shouts, laments, recitations and cries. Some people thrust themselves at the maqsura in exaltation, and those who clung to its bars and blocked access to the grave for too long were beaten with a bamboo stick. To get out one had to break through the stream pressing through the same narrow passage. This ritual, in which men and women participate together, resembles encircling The Kaaba in Mecca – this similarity irritates orthodox Muslims and is used by them as key evidence of the polytheism of Sufi brotherhoods.

Moinuddin Chishti Urs

Ajmer / 2014

The second image is a bit older and I observed it in India. A group of Sufi pilgrims from Indian Bengal reached Ajmer in Rajasthan and merged into the colourful march of people going on a pilgrimage from the various parts of the subcontinent. The lane led to the temple and the tomb (dargah) where one of the Sufi legends – Moinuddin Chishti, a mystic and philosopher who died in 1236 – is buried. Although flags of various sufi orders (tariqs) were carried by the colourful procession, it was not only attended by Muslims. Men and women of many Hindu religious groups and sects also attend annual pilgrimages and festivals (urs). There was also a big group of ornately dressed-up hijra – representatives of the third gender and worshipers of the goddess Bahuchara Mata – from Gujarat. In the vivid mystic tradition of the Indian Subcontinent to fully embody both male and female elements is a sign of either spiritual advancement or blessing. The hijras participating in urs are revered and feared at the same time because of their close relations with the criminal milieus.

The ecstatic crowd, chanting and high on marijuana and hashish, was greeted by the locals of Ajmer with a shower of rose petals constantly falling from windows to the pavements. After many stops to admire fakirs’ skills and acts of devotion (video below), the pilgrims reached the main gate of the temple, where they had been already expected by several rows of local Sufi officials in festive gowns. Then a large dhikr began spontaneously: after a while the entire gathering vibrated and rolled, charged with energy. It is impossible to describe this event, and because the lenses of my camera were soon misted up, this form of recording did not succeed. It was known that the pilgrims after dancing the dhikr were supposed to get into the temple; for this occasion two entrances with captions were prepared – resembling airport gates – one saying: MALE, and the other: FEMALE. The dhikr had not finished yet when a colourful wave of people split off to flood the entrance, completely engulfing the gates, security services and white-clad officials. The unstoppable charge, bristling with colourful flags, passed the temple courtyard and – to my surprise – instead of going to the main temple, headed for the cemetery inside the temple walls. The pilgrims settled on the graves of various minor Sufis associated with the Chishti brotherhood, lighted up chillums, and began singing and cheering. Urs in Ajmer, like Egyptian mulids, last six days and nights, and the dhikr is accompanied with never-ending qawwali chants. The moods of both is also quite similar, though there is definitely more joy, ease and liberty in urs. Egyptian festivals, rough and unpredictable, were until recently also characterized by greater madness and ecstatic character, but it has been gradually changing since the 1990’s when methods of regulation and control were found.

A common feature of the mulid commemorating al Sayyid Ahmad al-Rifa’i in Cairo and the urs at the grave of Moinuddin Chishti in Ajmer, India, which I had visited a few years before, was the fact that the character of both festivals was determined by events taking place in the maze of lanes around the tomb: tiny parties organized by pilgrims, eating together, drinking tea, smoking tobacco or chillum, conversations, entertainment, music, trance, celebration of the ubiquitous blessing, rather than the main narrative from a large stage or a consortium of well-dressed gentlemen speaking to a microphone. The festival is experienced through free navigation and participation in countless small celebrations. As a result of this immersion, the division into senders and recipients is blurred. Baraka floats in the air and is available to everyone and there is no need to add anything to it.

What makes Sufi festivals on every continent so unique is a ritual called dhikr – meaning ‘remembrance’ – being a crucial element of this tradition. The purpose of the ritual is to experience connection, and the altered state of consciousness, achieved in various ways, is intended to temporarily annihilate “ego” (fana’). Dhikr, a kind of icon of Sufism, is a broader topic that you will learn more about in one of my coming blog posts.

Egyptian Sufis usually visit one mulid a year, but some spend most of their lives participating in the festivals. From spring to autumn, when one festival ends somewhere, usually another begins in a different part of the country. This small but very characteristic group, known as dervishes, gives a clear message about life choices to average participants, proving that Sufism and mulid can be an alternative lifestyle, rather than just a several-day feast. Dervishes are full-time mystics living on the fringe of society, often homeless and without shelter. They are usually highly esteemed by other Sufis, although hardly anyone would really want to swap seats with them. But even the hard-working volunteers in Sufi khidma (service), running street kitchens in exchange for a bowl of rice, reject materialism and banality. Micro-utopias, in which average bread-eaters can experience a spiritual refreshment, are often established by the poor, the handicapped, and by single mothers traveling from one mulid to another with dervishes.

The character of both festivals was determined by events taking place in the maze of lanes around the tomb, […] rather than the main narrative from a large stage or a consortium of well-dressed gentlemen speaking to a microphone

CONTROVERSY

The order of everyday life is turned upside down by Sufi festivals. They are momentary utopias, a vision of a better world and liberation from the hegemony of purpose, meaning and all pragmatism. Ultimately, mulids are now becoming a political problem. The vision of the world they present cannot be reconciled with the vision shared by representatives of the modern middle class of Egypt: rational, ambitious, obeying religious obligations and prohibitions.

Salafists and members of the Muslim Brotherhood claim that mulids are bid’a (unauthorized innovation in Islam) introduced by the Fatimids, a dynasty initiated among the Algerian Berbers following the Shi’a Islam. The Fatimids conquered Egypt in the tenth century and established Cairo as the capital of their vast caliphate characterized by relative religious tolerance. The Salafist reformers feel particularly offended by the ecstatic dhikr as well as by the freedoms women enjoy during mulids. Salafists, fundamentally hostile to Sufism, criticize the worshipping of saints as a pagan practice and a departure from monotheism. The way they criticize mulids – sometimes considering them as backward superstitions, and other times as an innovation inconsistent with the orthodoxy – tells a lot about their vision of religion. Salafists interpret the Quran and hadiths as a religion of rational contemplation, in which work is a subject of worship, and piety is understood as observation of obligations and prohibitions. It is a distilled religiosity, devoid of all elements that do not fit into the concept of rational consciousness and ethics. It is not surprising, then, that ecstatic devotion, even a momentary loosening of borders, and dervishes – embodiment of utopia, wandering from one mulid to another – threaten their worldview. Sufism ignores the form (zahir) and focuses on the hidden mystical meaning (batin), preaching love, joy and tolerance. Therefore it also threatens more radical groups, making it difficult for them to recruit young people. In the north of Sinai, jihadists often devastate tombs and profane skeletons of Sufi saints. In November 2017, during the attack on the Jarir’iya Brotherhood in the al-Rawda Mosque, more than three hundred people, including almost thirty children, were murdered during Friday prayers.

Intellectual elites, nationalist circles and the modern middle class, in turn, see mulids primarily as the backward rites of a backward people. Just like in Europe, educated classes use a simplified description of the social structure. They control public debate and the media, unfairly delimitating borders and granting themselves a privileged status. They contrast themselves – as bearers of consciousness and knowledge – with “the street” (sha’bi culture), characterized by ignorance and superstitions. High culture and low culture. European Enlightenment is, alas, an indirect source of this chauvinism. Modern and progressive discourse lists the sanitary conditions – associated with presence of hundreds of people eating meals, relieving themselves and sleeping on the streets during festivals – as the grossest aspect of mulids. This disgust, however, covers the deeper grounds of their aversion. Mulids, by their very nature, are events undermining the very foundations of the modernist vision of society and state. A rational citizen cannot afford the ambivalence offered by Sufi festivals. Ambivalence does not serve the idea of progress and is an obstacle on the way to work.

It is interesting to analyse the issue of women’s emancipation in this context. In the rapidly modernizing Arab society, urban middle class women have access to education, they reveal their faces, loosen their hair and openly express their opinions. However, they belong to a group that actively strengthens the division into elites and masses by standing out strongly from their roots – often rural. Some new restrictions follow the privileges. It is not proper to eat in a cheap bar, go to the bazaar, visit the worse part of the city or the countryside. As a result, being a member of the upper class means functioning only in a selected, small fragment of Egyptian reality. From such a perspective, young girls from the poor district of Cairo, dressed up and celebrating each night of a mulid – in their own company and in the way they want – do not confirm the image of the conservative society restrained with its limitations. Restrictions do exist, but the divisions may look a little differently than we would like them to be to validate our vision of the world.

It is worth mentioning here that the tradition of circumcision of girls (chitan), which remains one of the biggest taboos of the Arab world, is not a custom limited to villages, but it is common among the middle class of Cairo and even the elites. The only difference is that in the city it is done not by a witch, but by a doctor in his/her surgery – after hours and in secret, because the government outlawed this practice several years ago.

women performing zikr

Moinuddin Chishti Urs

Ajmer / 2014

Female Egyptians were accepted as members of Sufi tariqs from the beginning of Islam until 1910, when the modernizing state took control over the most important brotherhoods and determined what was allowed and what was forbidden in Sufi practice. Many rituals were defined as being incompatible with the orthodox interpretation of the Quran and Tradition and fell into oblivion. The exclusion of women from participation in Sufi orders was one of the new rules, which was accepted, but not without great dispute and conflicts. Women, however, still exist in Egyptian Sufism – they are worshiped as saints, often unofficially occupy key roles in organization of large festivals, they are also members of smaller tariqs, too controversial to be legalized by the state and the High Council of the Sufi Brotherhoods. After the reforms, many women who were forbidden to participate in tariqs, joined and developed the Zār cult (more on this subject here), which has a lot in common with Sufism in Egypt, for example, presence of the same musicians. It is a paradox that restrictions on women’s participation in the mystical religious cult were introduced because of the modernization of Egypt in the twentieth century. The modern state produced new religious officials ready to reform religion and establish – almost without foundations – a clear division between what religion is and what it is not.

It is not my intention to diminish the achievements of currently active women’s organizations, which could be established due to dissemination of education by progressive forces in the Egyptian state. All I want is to undermine the over-confidence of Western observers – quite chauvinistic, regardless of their political sympathies – who praise liberalism and democracy as the universal remedy for traditionalism, backwardness and violence in the Middle East.

This approach is consistently represented by Piot Ibrahim Kalwas, a Polish writer and convert to Islam, residing in Alexandria. His book titled Egipt: haram halal – interesting and valuable, though biased – describes how the economic situation after the Yom Kippur War forced millions of men to leave Egypt, reforming dynamically under the rule of Gamal Abdel Nasser. They migrated for economic reasons to the east, to the countries of the Persian Gulf and to Saudi Arabia. Citing the book:

Besides money, they brought from there Wahhabite ideas of petro-sheikhs and religious sheikhs, which they transferred to the Egyptian soil, still relatively modernist and liberal.

This assumed superiority of modernism, liberalism and democracy makes Kalwas simplify reality and ignore phenomena that do not match the adopted perspective. He does not notice that in Egypt, modernism and rationalism of modern elites is a parallel complement to the “Islamic reformation” of the Salafi movement and the Muslim Brotherhood. A good citizen is a faithful Muslim. A modern state is an established order. Resident of such a country are civilized because they are rational, disciplined and observe the rules of the game. Ideal citizens are pious, hardworking, and they respect moral obligations and prohibitions.

Piotr Ibrahim Kalwas presents a vision of orthodox tradition, charged with violence, in the Wahhabite fashion, which does not necessarily coincide with the history of the Egyptian people. Wahhabism, the first distinct wave of reformation in Islam, appeared on the Arabian Peninsula in the eighteenth century. Members of the sect, followers of Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab, called themselves muwahhidun – literally: monotheists – thus implying that other Muslims’ faith was not monotheistic. Worshiping their saints, most Muslims of that time operated in a microcosm of various traditions, lifestyles and perceptions. According to Samuli Schielke, the reality of Egypt before the nineteenth century allowed much more ambiguity and madness than the norms of modern discourse allow. Modernism – both in Europe and the Middle East – established a state system that can be defined more adequately by the word “control” rather than by such terms as “freedom” or “equality”.

Mulids belong to this pre-modern reality, which turns out to be very liberal and flexible. According to Schielke, mulids in the period of Mamluk rule in Egypt, from the mid-thirteenth to the beginning of the sixteenth century, and later, when the country was a part of the Ottoman Empire, were much more subversive. Sessions of erotic dance performed by transvestites, ubiquitous prostitution and smoking hashish were the norm during festivals. Obviously, the frolics violating the then interpretation of Quranic law (sharia) were criticized, but usually understanding of the complexity of human nature and the calculation of religious, social and economic benefits prevailed. Restrictions on a larger scale began to be introduced just before the British occupation at the end of the nineteenth century, that is exactly from the time when the discourse of modernity settled in Egypt. Excesses during mulids and religious rituals incomprehensible to colonists suddenly became very risky. At that time, one who did not belong to a civilized world was a savage who could be legally exploited by the colonial powers. For the same reason, the pruning and formation of religion began to remove everything except pious contemplation, faith and morality.

The dawsa rite, crucial for the celebration of the mulid commemorating Prophet Muhammad in Cairo, was first to be attacked. The sheik of the Sad’iya brotherhood for the last time in history rode a horse on mystics lying in a row on the street, allowing the participants of the event to experience the action of grace (karamat). Apparently no one was injured. In the 1930’s in Tanta, during the largest Egyptian festival, a procession of prostitutes was held for the last time, and in the 1980’s, members of the Rifa’iya brotherhood, famous for their practices (video below), stopped puncturing their cheeks with sharp wires and charming snakes. Ziyara – the above-described ritual visit to the tomb of a saint – is disappearing from mulids all over Egypt, and screens separating the part for men from the part for women have been introduced in some mosques. In 2009, the Ministry of Health banned mulids commemorating Muslim and Christian saints for many months because of the swine flu epidemic; at the same time football matches and other mass events were organized without any obstructions. In 2017, a street parade during the celebration of Mawlid al-Nabi in Cairo was not allowed for safety reasons. Stages with platforms for speakers and rows of chairs are beginning to appear in front of temples…

Moinuddin Chishti Urs

Ajmer / 2014

The history of Egypt and the Middle East is not necessarily the terrible history of oppressive traditionalism currently being saved by rationalism, modernity, liberalism and democracy. Thomas John Newbold quoted – in his book The Gypsies of Egypt – a saying popular among residents of the nineteenth-century Cairo:

“If your neighbour,” say they, “has performed one hajj [a pilgrimage to Mecca – the author’s note], be suspicious of him; if two, avoid him; but if three, then by all means give up your house immediately, and seek another in some remote quarter.” [p. 286]

In observing mulids, one can see how a modern state, often more effectively than religion and folk tradition, limits freedom and sanctions behaviours in the public space. In the new reality, there is no place for an anti-hierarchical unpredictable festival at any time or place merging the sacred and the profane, the rational and the irrational. More importantly, in the new reality there is no place for an event that is in principle out of the control of political and religious elites. The temporary suspension of boundaries – with all its consequences – is the essence and the power of mulids.

Festivals at the graves of saints, unlike other Egyptian holidays, are not determined by the conservative order and they look like a celebration of joyful chaos. Mulids are a magical confusion liberating people from banality and – if banality is an element constituting the modern society – they can be regarded as a threat by this society. A pious citizen of a state composed of rational believers does not know many ways to respond to the laughter of a toothless madman with a disturbingly profound look in his eyes.

Luka Kumor, September 2019.

Translated from Polish by Andrzej Wojtasik.

SOURCES

Samuli Schielke, Perils of Joy, New York: Syracuse University Press, 2012;

Anna Madoeuf, Mulids of Cairo: Sufi Guilds, Popular Celebrations and the „Roller-Coaster Landscape” of the Resignified City, in: Cairo Cosmopolitan: Politics, Culture and Urban Space in the New Globalized Middle East, edited by D. Singerman, P. Amar, American University in Cairo Press, pp.465-487, 2006;

Stephanie Anne Boyle, Sheikhat and Haggat: Female Sufi Mystics in 19th Century Egypt, in: Sex and Sexuality in a Feminist World,edited by Katherine Hermes and Karen Riztenhoff, Cambridge University Press, 2009;

Michael Muhammad Knight, Magic in Islam, New York: Tarcher Perigee, 2016;

Bronislav Ostransky, Egyptian mawlids in the context of contemporary Sufi spirituality, Plzeň: Middle East in the Contemporary World Conference,2009;

Thomas John Newbold, The Gypsies of Egypt,„The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland” Vol. 16, 1856;

Idries Shah, The Sufi Mystery, New Delhi: Rupa&Co, 2007;

Piotr Ibrahim Kalwas, Egypt: haram halal, Warszawa: Instytut Reportażu, 2015;